Seeing differently at the LUMINA Center

Volunteer uses personal experience to teach students about low vision

-

Submitted photos

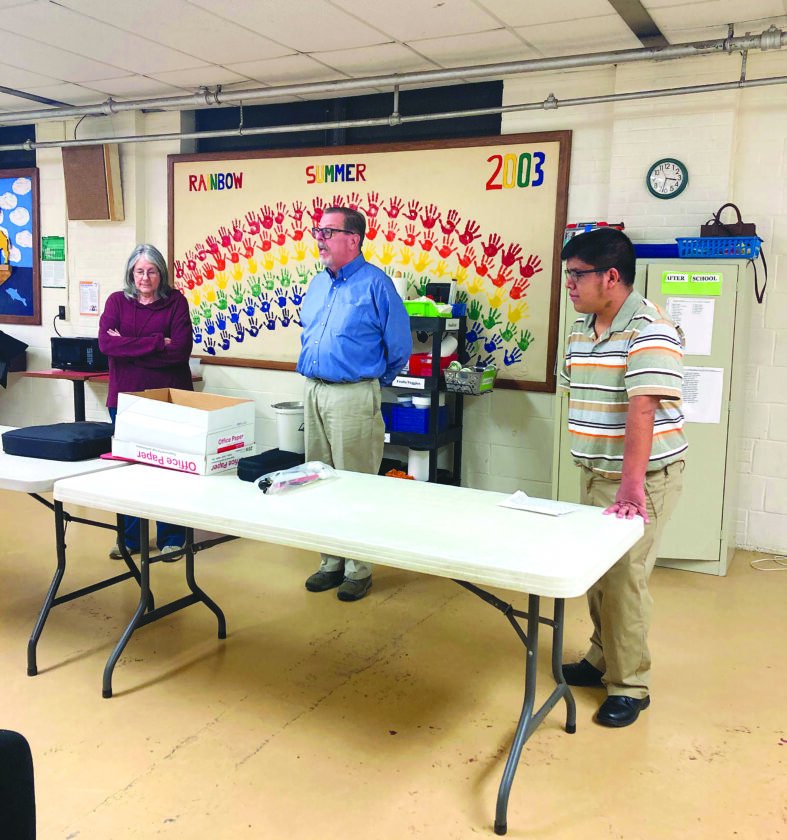

NuVision Director of Communications, Katie Long, case manager Randy Traxler and Victor Vazquez conduct a vision impairment presentation at the LUMINA Center.

Submitted photos

NuVision Director of Communications, Katie Long, case manager Randy Traxler and Victor Vazquez conduct a vision impairment presentation at the LUMINA Center.

LEWISTOWN — The white cane rested against a chair near the front of the room, easy to miss at first. A magnifier sat beside it. So did a phone, face down, waiting its turn.

Victor Vazquez stood before a small group of students at the LUMINA Center and began talking about how he sees the world — not in medical terms or abstractions, but plainly, the way people do when they want to be understood.

“For people who have normal vision, they can see things far away,” he said. “But for me, I have to be up closer in order to see things.”

Vazquez, a 2022 graduate of Mifflin County High School, has low vision. In his right eye, his vision measures 20/200. In his left, 20/160. Numbers like those can sound clinical and distant, so Vazquez translated them into daily life.

He can see people and objects from across a room, but he cannot read things from far away. He can see up close, but he needs large print — 18-point font or larger works best.

The presentation was part of a visit by NuVision Center staff to the LUMINA Center, which serves children through after-school and enrichment programs. The goal was simple: help students understand what vision impairment looks like in real life, become comfortable around unfamiliar devices and feel free to ask questions.

“It was important for students to hear from somebody like Victor instead of learning about it through a lesson,” said Katie Long, NuVision’s director of community services. “Learning from a peer almost always has greater impact.”

Vazquez was comfortable in the room. He volunteers at the LUMINA Center, working with children ages 6 to 9 in its after-school program. He has also volunteered at early learning centers in Lewistown and worked at summer camps.

Child care, he told the students, requires many of the same skills he uses every day — pouring food, cleaning and navigating space. His vision does not prevent him from completing daily living tasks.

One by one, he introduced the tools that help him.

The handheld magnifier drew the most attention. Vazquez demonstrated how he can take a photo of text and enlarge it to whatever size works — bigger, smaller or clear enough to make sense of words that would otherwise blur together.

“Once the kids saw what helps me make things easier,” he said later, “they were amazed.”

He talked about bump dots — small tactile markers placed on appliances like his microwave — that allow him to identify buttons by touch. He described adjusting computer screens, enlarging text on his phone and using transition lenses outdoors to reduce glare. When moving from indoors to outdoors, he said, he sometimes needs a few seconds for his lenses to adjust.

None of it was presented as extraordinary. It was simply how he goes about his day.

NuVision staff added context. Long and case manager Randy Traxler described other adaptive tools, including portable magnification devices that fold into compact units. Battery-operated, they can be carried from class to class and used to zoom in on whiteboards or printed materials.

“For young adults, the magnification devices are the big things,” Long said. “They’re game changers.”

The presentation also touched on eye care. Early and regular exams matter, Long said, because some conditions can be slowed or corrected if caught early. Once they progress beyond a certain point, treatment options become limited.

Students also learned about the law. In Pennsylvania, drivers must yield the right of way to pedestrians who are blind or visually impaired and carrying a visible white cane or accompanied by a guide dog. It was a small detail, but an important one.

Throughout the presentation, students listened closely and asked questions. Parents and aides leaned in. Long said the room’s attentiveness increased once Vazquez began sharing his personal experiences.

“Information is one thing,” she said. “But an experience shared from a known and trusted source is another.”

For Sherri Bickert, executive director of the LUMINA Center, that distinction mattered.

“People are often uncomfortable around individuals who act or look different, use unfamiliar devices or have special needs,” Bickert said. “This helps break down that discomfort. Victor helped our students see that people with special needs aren’t something to be afraid of or unsure about. He showed them it’s OK to ask questions and OK to treat people normally.”

Vazquez addressed that idea directly when he spoke to students about respect. He did not frame it as a lesson learned through hardship, but as something he had always been taught.

“To always treat people with respect,” he said. “And if you ever see anyone in school with a white cane, ask them, ‘Do you need any help with anything?'”

As the presentation ended, the tools were gathered. The cane was picked up. The magnifier slipped back into a bag. Students lingered, still talking.

Long hopes programs like this continue, not just for the information shared, but for what it signals to children.

“It shows them they’re important enough for people to come spend time with them,” she said. “To explain something they might not know a lot about. To answer their questions.”

Vazquez seemed content to have done what he came to do. He explained how he sees. He answered questions. He showed the tools that make his life easier.

The rest, he left to the room.